Taiwan’s Contiguous Zone: Why it matters and how it is under threat

Introduction

For the thousands of frustrated travellers facing delayed and cancelled flights between Taiwan and its outlying Matsu Islands and Kinmen, there may have been a sense of déjà vu. Last week’s multi-domain Justice Mission 2025 exercises were not the first occasion on which China’s large-scale military drills have disrupted civilian air routes in the region. Yet the increasingly routine character of such exercises should not obscure their significance, nor the ways in which they are challenging long-standing cross-Strait arrangements.

Beijing is, once again, testing a core element of the status quo that has underpinned a fragile peace across the Taiwan Strait for decades. This time, the focus is Taiwan’s contiguous zone – the 12-nautical-mile buffer surrounding its territorial waters. The steady normalisation of military activity within this space marks a subtle but consequential shift, one that lowers thresholds, increases the risk of miscalculation, and sets a potentially destabilising precedent for future Chinese military operations.

China’s Justice Mission 2025 exercises at a glance

After several months in which China’s large-scale military exercises around Taiwan appeared on brief hiatus, December 29-30 saw them return in full force. The Justice Mission 2025 exercises saw China’s People’s Liberation Army, Navy, Air Force and Rocket Forces combine to rehearse a full maritime blockade of Taiwan – establishing air and sea superiority, targeting key ports, and deterring external forces from entering the island chain. China’s Eastern Theater Command claimed the exercises a success, though it is not clear what metrics were being used.

Notable elements of the drill include:

The exercise covered a larger area than any of the previous five major war games conducted since August 2022, when then U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan.

Taiwan’s defence ministry tracked more than more than 130 aircraft sorties into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone, of which 90 crossed the Median Line through the Strait. This was the second highest number of PLAA sorties in 24 hours, only next to Joint Sword B 2024 (153 sorties).

The exercise also involved 14 warships and at least 15 coast guard and other official vessels. At least 11 warships and 8 coast guard vessels are reported as having crossed the contiguous zone boundary, 24 nautical miles from Taiwan’s coast line.

A total of 27 long range missiles were fired, with the impact zone near and around Taiwan’s contiguous zone. This is thought to be the closest landing that PLA missiles have made to Taiwan’s main island, though there was not a repeat of missiles fired over Taiwan’s main island, as in the August 2022 drills.

An image posted by official PLA accounts on social media claiming to show images taken by Chinese drones reaching as far as Taipei. These claims are widely believed to be false, with Taiwan’s government denying that drones entered Taiwan’s sovereign airspace during the exercise, but demonstrates the growing role that information warfare is playing in Beijing’s military strategy.

What is Taiwan’s contiguous zone?

Lost amid the unprecedented scale of the Justice Mission exercises is a more consequential development: China’s increasing targeting of the contiguous zone surrounding Taiwan’s main island.

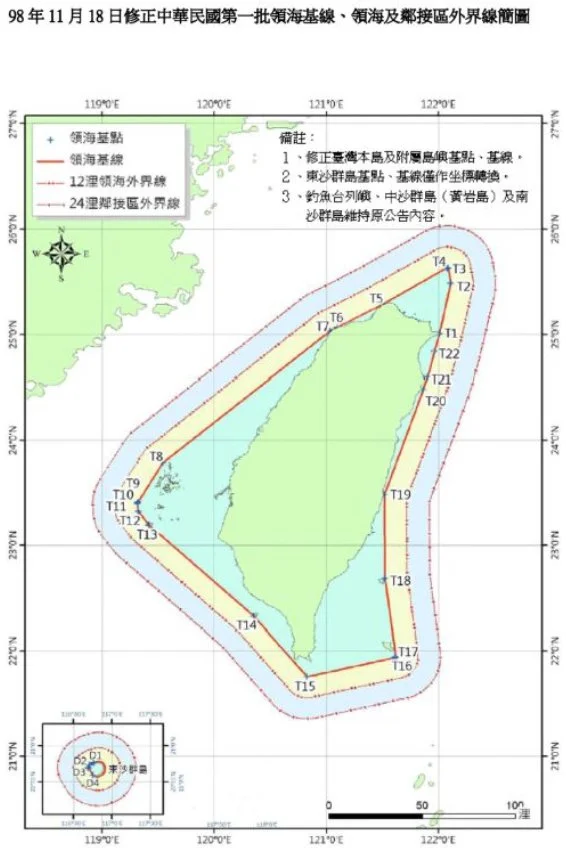

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the contiguous zone is a specific maritime area that sits beyond a state’s territorial sea but short of full international waters. A coastal state may claim a contiguous zone extending up to 24 nautical miles from its coastal baseline. Because the territorial sea extends 12 nautical miles, the contiguous zone effectively covers the area from 12 to 24 nautical miles offshore.

Although Taiwan is not a signatory to UNCLOS, and its statehood is not recognised by most UNCLOS members, Taiwan still exercises a de facto delineation of the 24 nautical mile boundary for the purposes of territorial defence and law enforcement. These boundaries are generally adhered to by maritime traffic passing through the region, and are not challenged by countries in the region other than China.

Map of Taiwan’s territorial sea and contiguous zone.

How has China targeted Taiwan’s contiguous zone?

While never formally acknowledged by Beijing, the contiguous zone was largely respected for decades, with Chinese naval and coast guard vessels generally avoiding it.

That pattern began to shift in the early 2020s, most notably with a sharp increase in the activity of quasi-military maritime research vessels. Taiwan saw nine intrusions into the contiguous zone by such vessels between September 2023, an increase from only two in each of the prior three years. The vessels were likely carrying out both civilian and military survey work.

Further, during China’s Joint Sword exercises in April 2023, over a dozen Chinese and Taiwanese vessels engaged in standoffs in at least 5 locations along the edge of Taiwan’s contiguous zone, including a brief incursion by a Chinese Type 052D destroyer. Last year’s Strait Thunder exercise in August 2025 saw a China Coast Guard vessel also enter the zone, reportedly reaching within 20 nautical miles of Taiwan’s main island.

The Justice Mission exercises marked the first instance in which Chinese military and coast guard vessels entered Taiwan’s contiguous zone in significant numbers. According to Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense, 11 People’s Liberation Army Navy vessels crossed into the zone, alongside eight China Coast Guard and other official vessels. In addition, 27 missiles were fired in or around the contiguous zone, although their precise impact locations have not been publicly disclosed.

In a notable flashpoint, one Chinese destroyer, Urumqi, reportedly withdrew only after a Taiwanese naval vessel applied a radar lock – a move which signals imminent capability to fire on the target.

Why does the contiguous zone matter?

While the distinction may appear technical, China’s efforts to encroach upon Taiwan’s contiguous zone is a direct challenge to one of the fundamental aspects of the current Cross-Strait status quo.

With the significance of the Median Line all but eradicated, the contiguous zone is the last remaining buffer zone between China’s coercive but sub-threshold military activity, and a direct hostile encroachment into Taiwan’s sovereign territory.

Taipei has made clear that any intrusion into its territorial airspace would be treated as a “first strike,” reserving the right to respond with force. No equivalent red line has been articulated for the contiguous zone, which has instead functioned as a critical final buffer to manage risk and prevent escalation.

If that buffer is gradually erased, the dangers multiply. Military drills conducted closer to Taiwan’s sovereign waters may be interpreted as actual attacks, heightening opportunities for miscalculation and unintended escalation. Alternatively, actual attacks might be initially misinterpreted as drills, reducing Taiwan’s response time and weakening its response. Either way, sustained activities in the contiguous zone pushes ever closer to Taiwan’s red lines, increasing the chances of provoking a military response.

If China does succeed in normalising military activity in Taiwan’s contiguous zone – as it has succeeded in normalising military activity across Taiwan’s side of the Median Line – the obvious next step in China’s escalatory logic would be to extend such activities into Taiwan’s territorial waters. At this point Taiwan is left with a very stark choice between conflict and capitulation. No island state can claim to exercise sovereignty without exclusive control of its immediate surrounding waters. Either Taiwan proceeds to expel Chinese encroachments by force, or it concedes to China’s demands for a negotiated annexation. Neither outcome is in the UK’s strategic interests.

How should governments respond?

Time is running out to uphold Taiwan’s Contiguous Zone, and the fragile status quo that it underpins. The Justice Mission exercises are China’s clearest statement of intent yet that it intends to eradicate this last buffer zone, no matter how escalatory or dangerous this could prove to be.

Yet none of this urgency is reflected in the short statements issued by Taiwan’s closest partners. U.S. President Donald Trump, for example, said that “nothing worries me” about the drills, noting that China had been conducting naval exercises in the area “for 20 years.” Statements from other G7 partners including Australia, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, largely reiterated familiar calls for restraint and the peaceful resolution of disputes, without addressing the escalated risks posed by the normalization of activity within Taiwan’s contiguous zone. The UK statement does not mention the contiguous zone at all, and a few slight tweaks aside, is effectively a ‘copy and paste’ of previous statements.

Taiwan’s partners must act urgently to uphold peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait, and their broader strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific region as a whole:

Governments must do a better job of defining the ‘status quo’: The G7 and other countries have repeatedly voiced their opposition to any unilateral change to the status quo, without clearly defining what the status quo is, or explicitly acknowledging the ways in which it has already been undermined. The importance of the contiguous zone to the status quo is just one example. While most governments are unlikely to formally recognise Taiwan’s contiguous zone, they can still highlight the importance of respecting such de facto boundaries as critical to maintaining the status quo.

‘Copy and paste’ statements are not working: While it is encouraging that the G7 and other countries have consistently put out statements in response to China’s large-scale exercises around Taiwan, the scant and recycled language fails to reflect the ways in which successive drills are exhibiting increasingly escalatory actions from Beijing. While carefully worded official formulations of longstanding policies towards China and Taiwan may not change, statements can still highlight particular points of concern around particular activities in particular drills. Doing so ensures that governments are clearly signalling their opposition to China’s escalatory actions, rather than a routine response to routine drills.

Taiwan’s partners need a coordinated sub-threshold response: That China is infringing upon the contiguous zone in such numbers is not unexpected – we at CSRI highlighted this possibility in our paper Mapping out the UK’s Response to Grey Zone Escalations against Taiwan in May 2024. We recommended the UK and its allies seek to raise the costs to China of conducting sub-threshold coercion against Taiwan, in proportion with China’s escalations. Limited sanctions on China’s military linked companies, increased engagements with Taiwan, and supporting Taiwan’s efforts to build its resilience and defensive capabilities, can all be effectively leveraged as proportionate responses to sub-threshold coercion.